Lotion in the ocean: is your sunscreen killing the sea?

Up to 14,000 tonnes ends up in coral reef areas each year, but scientists are divided on how we can best protect our skin without harming the environment

Autumn Blum was 5 metres underwater, scuba diving off the Pacific island of Palau, when she looked up towards the surface and saw a rainbow.

“I thought maybe it had been raining,” she says. “As I got closer, I saw that it wasn’t a rainbow: it was actually an oily sheen that was coming off a group of snorkellers.”

She realised the iridescent slick must have come from the snorkellers’ sunscreen.

“When I got back on the boat, I picked up the closest bottle of sunscreen and was reading the ingredients,” she says. As well as being an experienced diver, Blum is a cosmetics scientist who has created natural product brands. These were ingredients she would never put in her own products, “and yet here we were using these ingredients in the most sensitive marine environment in the world”.

Sunscreen is essential to protect skin against cancer, and with many pandemic-related travel restrictions around the world starting to lift, sales are expected to rocket. In recent years, however, it has also come under scrutiny for being potentially toxic to the environment – especially the oceans in which sunscreen-slathered tourists swim.

Estimates vary about how much sunscreen makes it into our oceans each year. Cinzia Corinaldesi, associate professor of ecology at the Polytechnic University of Marche in Ancona, Italy, has estimated that 20,000 tonnes is washed off tourists every year in the northern Mediterranean alone, while Dr Craig Downs, another leading researcher and the head of nonprofit scientific organisation Haereticus Environmental Laboratory, thinks that between 6,000 and 14,000 tonnes are released annually in coral reef areas each year.

The focus has been on two chemicals, the ultraviolet filters oxybenzone and octinoxate, though there are other troubling ingredients. Hawaii banned those UV filters from January this year, and in 2018 Palau announced broader restrictions on sunscreens containing a number of chemicals. Other regions have similar bans.

But with switched-on consumers seeking out “reef-friendly” brands that, in the absence of any strict definition, may or may not be reef-friendly, and some marine experts arguing that the negative effects of sunscreen have been overstated or don’t exist, there is huge scope for confusion.

Corinaldesi is one of the scientists convinced of the toxicity of many sunscreens. She has been studying the impact of sunscreen on marine environments since the early 2000s.

“We were inspired by the fact that in Mexico, at the cenotes [natural swimming holes], it was forbidden to use sunscreen products before diving into the water,” she says. “Mexicans had noticed that [it affected] the delicate life forms of these fragile ecosystems.” Corinaldesi and her marine biologist colleagues started conducting research in coral reef areas around the world, to observe the effects of the chemicals in sunscreen.

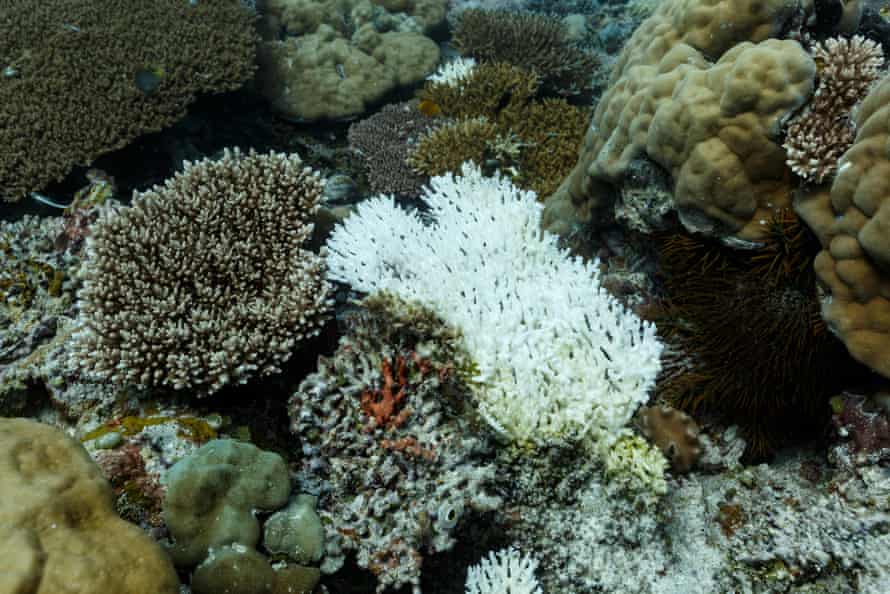

“We showed, for the first time,” she says, that some filters and preservatives “caused complete coral bleaching even at very low concentrations. Since then, we have continued to test several [sunscreens], including some ‘eco-friendly’ products, on different marine organisms and have found that some sun products cause abnormalities in embryos and larvae.”

This included “irreversible damage” to the development of the sea urchin. More work, such as the research published by Downs in 2015, found oxybenzone was fatal to coral larvae.

While we may think the bit of sunscreen we use at the beach (and dermatologists say we routinely under-use sunscreen) can’t have much impact compared with the vastness of the ocean, Downs’ study suggested oxybenzone had a detrimental impact at 62 parts per trillion – the equivalent of one drop in six and a half Olympic-sized swimming pools.

“Any coastal area, especially in summer when beaches are crowded, is at risk, particularly in shallow waters where sunscreen concentrations can reach relatively high levels,” says Corinaldesi.

While the impact on coral reefs has attracted the most attention, other marine life may be affected, including “phytoplankton, small crustaceans, molluscs and fish, which support food webs, and other organisms such as sea urchins, which are ecosystem engineers and essential for the creation of marine habitats.”

It isn’t just UV filters that are of concern. Dr Francesca Bevan, chemicals policy and advocacy manager of the Marine Conservation Society (MCS), says PFAS (perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl) chemicals, known as “for ever chemicals” because they take so long to degrade, are still found in some cosmetics and products, including sunscreen, despite an incoming EU ban in non-essential use. These chemicals don’t just wash into the sea – they can also trickle into waterways when you shower them away at home. PFAS chemicals “are so mobile in the environment that they’ve been found in the Arctic, and places that are ridiculously far from any human activity. It shows they can move around the world,” says Bevan.

The MCS has started looking into the effects of sunscreen, Bevan says, adding: “With climate change, sunscreen use is only going to go up, and people are a lot more aware of sun damage and skin cancer.”

Rather than smearing it top to toe, she suggests seeking shade and covering up with clothes, with sunscreen used only on the smaller exposed areas of skin, adding: “Limiting the use of any harmful chemicals would be a good thing.”

Many sunscreens are marketed as “reef safe”. Mineral sunscreens, which often use zinc oxide as a physical UV shield, have been promoted as an alternative – which Corinaldesi herself has argued for. But she says new evidence is emerging that suggests they, too, may cause some harm.

“Further studies we carried out indicate that mineral filters such as zinc oxide nanoparticles cause rapid coral bleaching and also damage the algae that live with them, as well as damage the developmental stages of many marine species,” she says.

Corinaldesi now advises people to avoid products containing several ingredients including oxybenzone, octinoxate and octocrylene. She also says to avoid nano-sized zinc oxide in mineral sunscreen, and recommends to look for independently tested brands.

It’s not easy for consumers to decipher all this, and there are also other barriers, beside their higher cost: many mineral sunscreens leave a white cast, which can be especially noticeable on darker skin. (It’s the use of nanoparticles that reduces the whiteness.)

It may all be in vain anyway – or at least a distraction from the real problems.

“The three main threats to coral reefs are global warming, overfishing and coastal water pollution,” says Prof Terry Hughes, former director of the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at Queensland’s James Cook University, and one of the world’s leading coral reef experts. “Coral bleaching is triggered by rising temperatures due primarily to burning fossil fuels. We have already seen three global-scale coral bleaching events due to record-breaking heatwaves, in 1998, 2010 and 2015-2016, which affected 50-70% of tropical reefs. Even the most remote reefs, far from mass tourism or sunscreen, are affected by global warming. There is no scientific evidence that use of sunscreens by people has a harmful effect on coral reefs.”

The studies showing a link between sunscreen and harm to coral have largely been done in “unrealistic lab experiments”, says Hughes. Switching to a “reef-safe” sunscreen may make people feel they’re doing enough, when “realistically, tourists could support reefs a lot more by flying less, and especially by voting for politicians who’ll take urgent action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Fighting climate change is the key to reducing the global threat of coral bleaching.”

Corinaldesi acknowledges that “the impact of global climate change on coral reefs is the main problem, [as well as] pollution, overfishing and the spreading of viral and bacterial diseases”. But she believes that the chemicals we use in products such as sunscreen may worsen their effects.

After her diving trip to Palau, Blum worked on several new products, including sunscreen, that have a lower impact on the environment. “I’m not going to say that sunscreen is the number-one contributor to coral decline,” she says, “but it’s a very easy one that we can eliminate.”